Nazi Germany, 980 planned, 61 completed (1944-45)

Nazi Germany, 980 planned, 61 completed (1944-45)WW2 U-Boats:

Seeteufel (1944) | Type Ia U-Boats (1936) | Type II U-Boats (1935) | Type IX U-Boats (1936) | Type VII U-Boats (1933) | Type XB U-Boats (1941) | Type XIV U-Boats (1941) | Type XVIII U-Boats (1944) | Type XXI U-Boats (1944) | Type XXIII U-Boats (1944) | German mini-subs and human torpedoesThe true Elektroboot

The Type XXI were large scale production Kriegsmarine’s “wunderwaffe” planned by Nazi Germany at the end of the war. Alongside the smaller Type XXIII “Elektobote” and numerous “midgets” at a stage events verged on desperation, the Type XXIII was also supposed to reverse the situation. Announced as the boldest leap into the future for the Kriegsmarine so far, the world’s most advanced submarine design of their time, The Type XXI would be also a powerful inspiration for all navies in the next decades, and up to the 1957 USS Nautilus. In the end an order for 980, then 280 was down to 61 U-Boats of type completed, commissioned, but only a few had a meaningful operational career, with seven lost in action and a relatively low tonnage sunk. So was it a real game changer in 1945, or just an overblown propaganda effort ? Here’s the detailed answer. #kriesgmarine #uboat #germannavy #ww2 #typeXXIII #walterturbine

BDMS Hecht S-171 in the 1960s, the only sailing Type XXIII in the cold war. She was the former sunken U-2367, raised, repaired and modernized. She was used to rebuilt both engineering and crew’s skills. With her ill-fated sister Hai (S-170) she was at the base of cold war German submarine development. They were followed-up by the U-200/201 types (pinterest).

A technological revolution: From submersible to submarine

The move towards “submersibles” to “submarines” was done during WW2, but never realized in practice, despite the fact Nazi Germany tried hard to gather resources for it to happen. The difference was considerable as with the common model, U-Boat Type VIIC that roamed the Atlantic from 1940, was essentially the same model as the WWI mass-produced (92 on 129 planned) Type UB III, which was a simple mid-range model, mass-produced until 1945, surfaced most of the time, only submerging in emergency. The transition towards a “submarine” meant to simplify having greater characteristics to stay and perform better underwater. Doubling the speed and depth to escape escorts, and stay underwater, so undetected for much longer, were the prime objectives. Given the limitations of electric power at the time, it was necessary to forge out looking for a new power source than the traditional diesel-electric.

The conclusion of all reports for losses to the allies were plural in origin: More escorts, more ships to sink (Libery/Victory), better tactics, better detection system, better armament, constant naval aviation patrol, and unbeknownst to the German naval staff, full knowledge of impending attacks thanks to the breaking of the Enigma machine by the Turing computer at Bletchley Park.

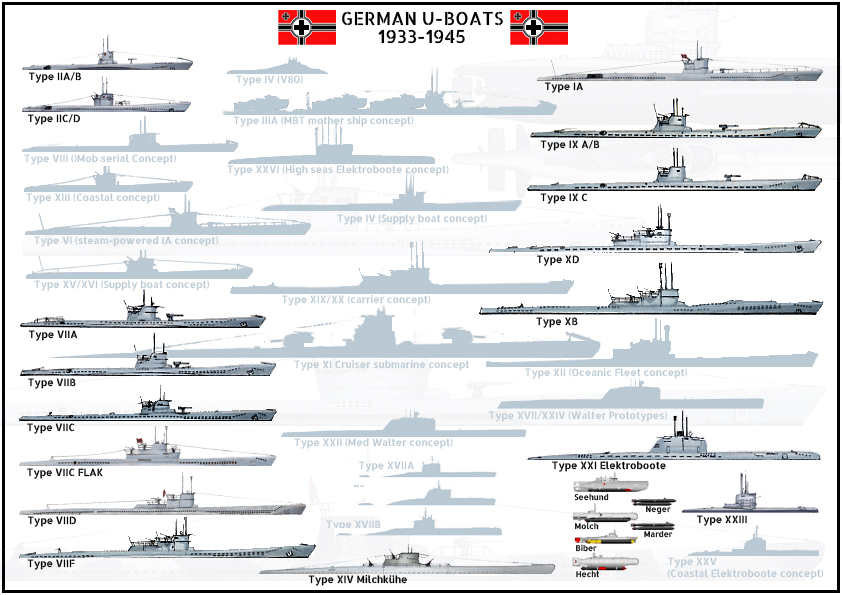

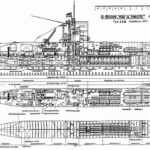

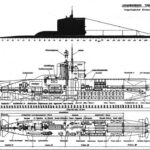

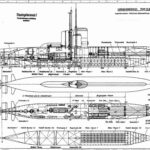

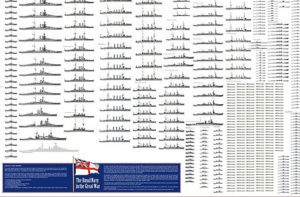

Author’s illustration depicting all types, produced, tested and paper projected of German Unterseeboote during the war. Greyed out profile are approximations based on available information, of paper project or submarines started but never completed (like the Type XXV boats). This does not give the scale of production however. Note the Type XXIII scale on the down right corner, below the Type XXI.

But Hitler was convinced by Kark Dönitz, at the head of the Kriegsmarine in 1943, to invest massively in new AIP experiments by Dr. Walter to allow a submarine to be submerged almost indefinitely and thus, having a new “secret weapon” that could turn the tables. In the comparison between the Heer, Luftwaffe and the always “poor child”, the Kriegsmarine, and some help by Albert Speer to set a mass production in 1944 it was hoped to produced two models, one for coastal operations (The Type XXIII) and one for oceanic operations (Type XXI). The latter was a replacement for the now obsolescent Type VII, the former to replace the early Type I, II and III midget U-Boats of the interwar.

Albert Speer, Karl Dönitz and Alfred Jodl in 1945.

Unfortunately Dr.Walter experiments, which led to some excellent results, were in the end not considered worth an adoption in submarines by wartime, as the chemical compounds used were way too volatile and dangerous. A depth charge detonation could have trigerred notably an internal explosion. As development dragged on and without a workable powerplant at hand, Dönitz decided to compromise to launch production, by essentially doubling the battery capacity and keeping trusted diesels, a snorkel, while integrating many other innovations, which, combined with the modular construction, were a lot to manage under constant allied raids over Germany by 1944-45. In the end, only 118 Type XXI were completed over 1,170 planned, and the only two operational achieved nothing during their sorties.

Dönitz however had an “ace” perhaps more appropriate to the war as it evolved after D-Day and the loss of French and Dutch ports. To answer the evolving situation, a two-prone solution was given, using human torpedoes and midget submarines on one hand, provided they could be trucked or brought by rail close to deployment (this too, was a failure), and the new coastal Type XXIII, which had just enough range to leave Baltic ports, cross the Skagerrak and operate in the north sea.

Development

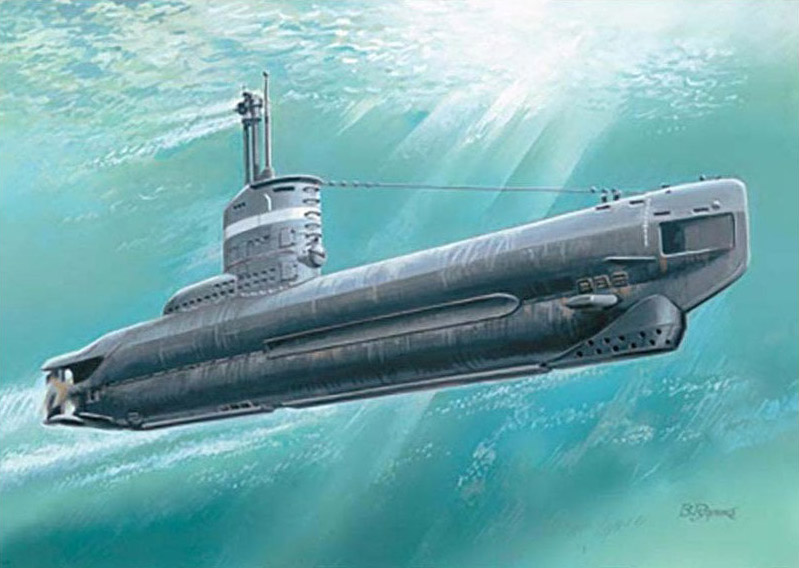

Model of the Type

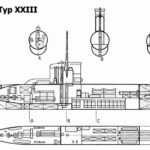

The German Type XXIII so-called elektroboote (“electric boats”) were designed as cheap, small coastal submarines for shallow waters and not initially limited to the North Sea, but also intended for the Black Sea and Mediterranean, the use of railways and modular assembly being crucial in that strategy. Albeit in great lines they shared the same very large battery power to be faster, and stay longer underwater, they were very rudimentary, lacking all the innovations ported on the Type XXI, and could carry only two spare torpedoes, which in addition could only be loaded externally. Still, engineers worked on improving their streamlining and there was a snorkel, to run on diesels all the way to the deployment area, given the allied air superiority. The Type XXIII was still advanced enough to inspire post-war submarine design, such as the Soviet Quebec class. Indistrial plans were just as ambitious as for the Type XII, with the same elaborated modular construction spread into many sites to avoid bombing, and final assembly in a bunker. Type XXIII boats however arrived also too late, the bulk being cancelled, scrapped incomplete, and just paper projected. There were also plan for even smaller boats (see later). Still, they were more advanced and larger than the Seehund.

Development on the Type XXI U-boat started late 1942, just when it was decided to double on a smaller, cheaper version with the same advanced technology, at first specifically to replace the Type II coastal submarine. Karl Dönitz at the time, as the situation of the axis was still largely, wanted them to operate in the Mediterranean and Black Sea, and for this, rail transport was a necessity. It was already the case for WWI U-Boats. The other obligation as specified was the use of the very same standard 53.3 cm (21 in) torpedo tubes to be able to fire more advanced acoustic/electromagnetic torpedoes that were planned. So even only two torpedoes had far more chances to get a hit.

The development of the Type XXIII was later given higher priority, and Speer revised it to use existing components as much as possible to reduce development time, while Helmut Walter in charge of the project recycled the previous Type XXII prototype’s hull. By 30 June 1943, the design was ready for approval. Construction was setup at several shipyards between Germany, France, Italy and Ukraine all under supervision of the lead contractor Deutsche Werft, in Hamburg.

The major manufacturing challenge was to have them constructed in sections, with a final assembly that was as easy as possible with limited expertise or resources. Modules were to be produced by different subcontractors, in open facilities, and later by mid-1944 from inside mines and other underground facilities. Some foreign yards were given the responsibility to assemble U-2446 to U-2460 at Nikolaev in Southern Ukraine under supervision of the Deutsche Werft yard. They were moved to the Linzner yard as the situation evolved, on 1 May 1944 but later cancelled. In late 1944 construction was entirely concentrated at Germaniawerft, Kiel and Deutsche Werft, Hamburg, the first managing to assemble 51 and Deutsche Werft 49 Type XXIIIs. The initial plan for 980 being dropped and reduced to 280, 61 were completed, commissioned but due to training time, only 6 ever carried out a war patrol. This was better than the Type XXI anyway.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

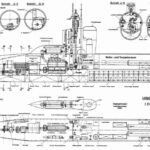

Open source rendition, creative commons

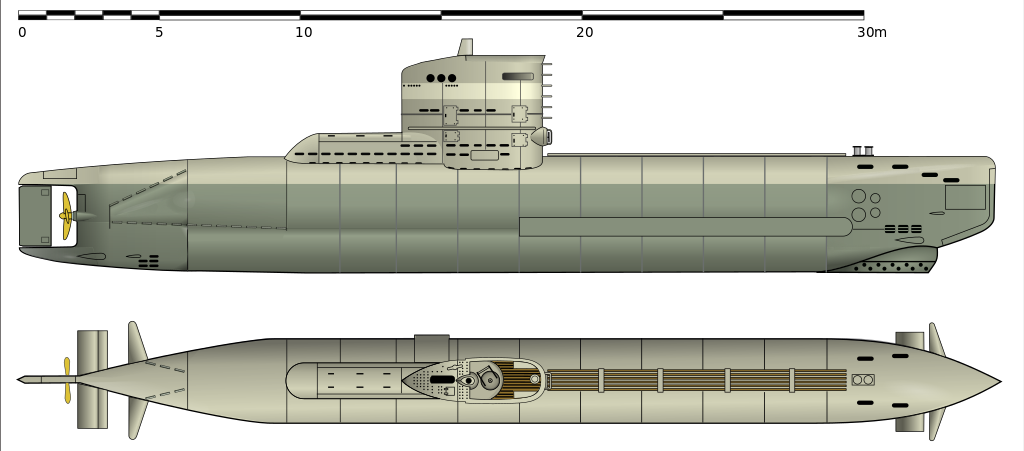

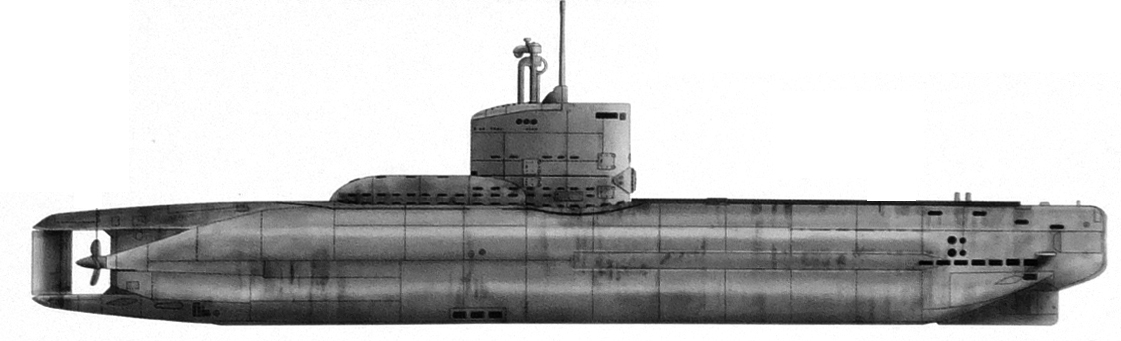

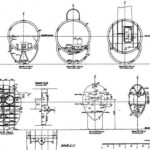

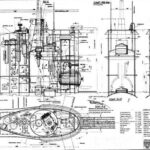

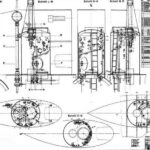

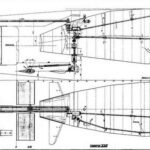

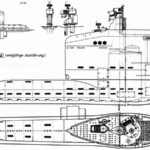

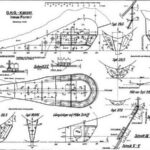

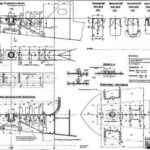

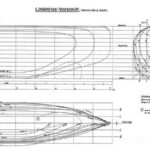

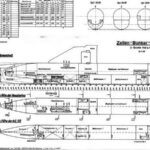

The Type XXIII had an all-welded single hull, a world’s first, with a fully streamlined outer casing, relatively small conning tower (simplified and les advanced than the Type XXI’s) and she had a fairing housing the Diesel exhaust silencer. He hull “deck” was uncluttered and well shaped for the best underwater speeds, as the straight stem. Walter design did not included no forward hydroplanes as it was believed the aft rudders and blowers were sufficient, but they were added later.

Another simplification was a use of a single three-bladed propeller, one shaft, plus steering via a single rudder. She had a halved machinery compared ti the Type XXI but reused iuts “8” shaped shull anyway, its smaller lower section, difficult to access, housing the very large 62-cell battery. The double cylinder shape for a pressure hull was not surprising as it was the better suited shape to resist pressure.

Eaquipment was barebones. There was a single periscope, a “Bali” radar warning antenna but no radar, no torpedo reloads, and the listening device was simplified with 2×11 membrane receivers, and no active sonar.

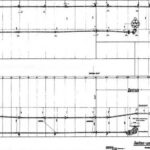

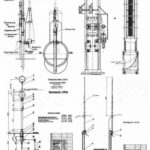

Since original documentation had been burned, the only existing plans are those reconstituted by the Bundesmarine after refloating the two U-Boats later modernized as Hai and Hecht.

Construction and assembly

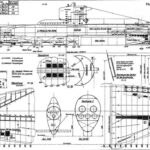

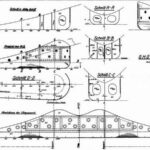

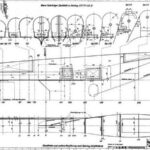

In order to be ready for rail transportation, the hull was divided in four sections fitting the standard loading gauge of the time, which was the same throughout Europe but not Russia. Sections were tall and carried either vertically between supports, or laid down on the side due to the issue of tunnels. Thus, four sections plus the conning tower were carried, each on their own flatcar. A full train, often added one or two Flak cars of ten plus the locomotive could carry two knocked-on Type XXIII for final assembly wherever necessary.

The fully assembled boat displaced 234 t (258 short tons) surfaced and 258 t (284 short tons) submerged for an overall lenght of 34.68 m (113 ft 9+1⁄2 in), a Beam of 3.02 m (9 ft 11 in) and a Draft of 3.66 m (12 ft). The whole height from keel to conning tower was c7 meters or 23 feet. Each section was roughly eight meters long, compatible with most twin bogie flatcars.

Rough sections were supposed to be assembled in foreign yards, but planned operational space and requirements for transportability changed, so when weight was checked, engineers were alarmed as the completed boats were too heavy and no longer buoyant, due to all the additional equipment required by the Navy. This created significant delays as it was necessary to insert a 2.20 meter long intermediate piece (“Oelfken”) section to just recover this buoyancy, an extension of 1.30 meters. Dönitz wanted to have two reserve torpedoes carried but due to the bow compartment internal loading redesign, creating further delays the shipbuilding commission rejected it. External loading with iron frame and trimming became the norm. Construction costs at Finkenwerder were estimated at 761,721 RM per boat.

Diving performances

The Typ XXIII had a diving depth of 100 meters (2.5 times safety) but a test diving depth of 150 meters and destruction depth, calculated at 250 meters. The pressure hull plating was made of shipbuilding steel St 52 KM, 9.5 mm to 11.5 mm thick but stiffened by 140×7 mm for the flat bead inner frames interleaved between 450 and 550 mm. The St 52 was chosen because ot was easy to weld and became a standard in German submarine construction until the end of the war: It had a yield point of 360 N/mm² and strength of 520 N/mm². The outer hull’s frames and skin were made of lighter St 42 KM, also welded.

The pressure hull consisted of two cylindrical halves placed together at the front and amidships the lower space housing the battery cells (diameter 2.80 m) whereas the living quatters above were inside the 3.00 meters diameter tube. The pressure hull was 22.5 meters long. All diving cells and fuel oil bunkers were located in the outer hull.

From April 1944, an increase in carbon and silicon content of steel St 52 was ordered in order to save manganese. From August 1944, thus, cracks were expected to form during welding after a three-month delay. The order was immediately revoked but not take effect until spring 1945, delayng the whole proghram and casting doubts about the early boats. On October 2nd, after a tour of Germania shipyard, Vice Admiral Friedrich Ruge noted “Poor welding” was visible.

Stresses on the pressure hull when diving were calculated at IBG bye engineers Schubert, Kuhlmann and Wüpper adn they depended on various section, with an empirical coefficient of 0.8 from 25.6 to 28.8 kg/cm². They published a watning on the matter on December 6, 1944 but confidence still, was great for the “8” shape. The calculations were done on a single tube, now two tubes connected together and only a deep diving test chould confirm this. This was done on January 24, 1945, by U 2324 off Norway with special dial gauges recorders and tension wires, plus fully loaded. At 150 meters, cracking noises were heard and she was kept the boat at this depth recoding 7.35 kg/mm³ and the commander refused to go deeper and surfaced. Postwar, U 2326 was lost with its French crew on December 6, 1946 during a deep diving test at 165 meters so beyond a probable destruction depth of 160 meters according to the Lübeck engineering office, which also worked on Hai and U Hecht postwar. The safety depth was set at 65 meters, max test depth at 80 meters.

Powerplant

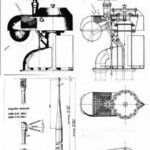

Since the Walter AIP propulsion was never ready, a rather conservative approach was taken, with the use of one MWM RS134S 6-cylinder diesel engine rated for 575–630 metric horsepower (423–463 kW; 567–621 shp) coupled with an AEG GU4463-8 double-acting electric motor, rated for 580 metric horsepower (427 kW; 572 shp) and for silent apoproach, a BBC CCR188 electric creeping motor, 35 metric horsepower (26 kW; 35 shp). As said aboven there was a 62-cell battery power and the diesel could be exhausted and fed b air coming from an advanced snorkel. The latter was not perfect, and ingested water even in moderately rough seas.

Due to friction losses in the gearbox, reduced to 2.835:1 due to the speed diffencial bertween the diesel/main electric motor and propeller, only 95.5% of engine output was truly passed on to the propeller screw and when running on diesel the absolute down limit was 5 knots due to its sooting.

Top Speed was thus of 9.7 kn (18.0 km/h) surfaced and 12.5 knots (23 km/h) submerged for a 2,600 nmi (4,800 km) at 8 kn (15 km/h) range surfaced and a total of 194 nmi (359 km) at 4 kn (7 km/h) submerged, far enough for approaching dense sea lanes in safety. Test depth was 180 m (590 ft) as calculated. Of course the modules assembly was a crucial factor of strenght, linked to welding skills, but each had its own thick bulkhead.

Snorkel Running

Unlike on the larger Class XXI submarine, the similar snorkel system of the Type XXIII operated well. The diesel engine was large and well fed enough for performance achieved while snorkeling with an intake vacuum 38 mbar, exhaust pressure of 0.35 atm. Both snorkel and periscope were vibration-free at all speeds. Max snorkeling speed was even higher than full surface speed due to the lower resistance encountered, at 10.75 knots. Detection by enemy radar could be reduced to 30% when snorkelling and only 10% whej the snorkel was padded with a special rubber-like covering (“Chimney Sweep”). This coating was developed by Johannes Jaumann with IG Farben by the spring of 1944. Like an onion it was multi-layered with various thicknesses down to the metal wall of the snorkel. In addition individual layers were separated by dielectric support layers having a very low dielectric constant. Radar waves were thus absorbed in depth and became weaker and slower with its energy completely converted into heat. Fortunately, ships had the time had no infrared detection systems. The coating was studied by the allies postwar and called “a radar swamp”, the principle is still used today on modern SSNs. In addition the Type XXIII when snorkelling had detection warning with the pressure-resistant decimeter wave antenna “Bali 1”.

It did not worked on higher-frequency centimeter-wave radars.

But these were problems: This telescopic snorkel needed 27 seconds using compressed air however to be raised and down, and the system was unreliable and very noisy. It had manual backup through. The snorkel head used a float-operated head valve supposed to close automatically when flooded but it was not the case in operation. They failed in specific course in relation to waves directions. In cold water there was no meas to prevent icing as well. Onboard listening device when snorkelling was inoperative due to parasiting diesel noise while in return, the Type XXIII could be detected from 8,000 meters. Captains were instructed to interrupt their run every 20 to 40 minutes just to listen. The submarine then went on by inertia and the diesel was restarted as speed died out after just a minute. So this did not hampered much its course.

Electric silent running

When providing electric power as used as generators the main electric motor was able to deliver 1280 Ampers at 300 volts. When driving at slow speed only on its main electric motor, noise of the main machine gearbox was critical. Thus the use of a creeping motor was necessary depending on the mission. Top speed underwater was geared down 3:1 by a V-belt at 4.8 knots, with a maximum crawl speed sustained at 4.3 kn for 30 hours with a fully charged battery. At 2.5 knots, range reached 215 nautical miles or 398 km.

At almost all speeds achievable with the slow speed drive, these boats were very stealthy, almost impossible to detect with standard acoustic devices of the time in 1944. At a diving depth of 11 meters and from 500 meters of any liseting device, the noise at 120 rpm was less than 26 dB at a water value of 1 µPa unlike airborne sound (20 µPa). Eaquivalent air sound pressure was 0 dB so barely a human sound respiration.

U 2321 achieved 4.8 kn under 20 meters, at 28 kW on shaft, a crawling speed twice as high as the Type VIIC. At max crawl speed cavitation noises spilled the bill, but it was worked out by thickeining the propeller tip edges to the cost of 0.3 kn. This change became standard.

Innovative double Batteries

The battery system comprised two lead accumulator and an innovation, 31 double cells of the 2×21 MAL 740 E/23 type to produced a current between 240 and 120 volts with fewer cells. Each double cell weighted 598 kg and worked at 30°C to generate 2176 Amper for a total capacity of 3264 Ah and 1.5 hours of discharge time or 874 A and 5 hours of discharge time, down to 116 A and 50 hours discharge, average discharge voltage of 2.0 volts per cell for a total of 1.3 megawatt hours. Current consumption was 1960 A in daily operation.

Battery charging started at 980 A up (2.4 volts per cell, 149 volts per half battery) and in the second charging stage down to 245 A/2.4 volts per cell. Third stage it was 245 A to 2.7 volts but fast charging was not recommended due to heat issues. Ventilation was not adequate. Full charging time after full discharge in 3 hours needed 6.75 hours of charge in two stages, the third only be recommended once a week to maintain capacity. They released explosive oxyhydrogen via electrolysis, realing up to 19 m³ of gas per hour when in use, so a working ventilation adjusted to suck out 59 liters of oxyhydrogen mixture were necessary for each battery cell per minute at 245 A.

Performances: Agile but dangerous boats

The Type XXIII as tested in 1944 proved to have excellent handling characteristics. It was highly maneuverable while surface and underwater, and this was all due to Walter’s skills in streamlining it. It was able to crash dive time in just 9 seconds, so enough to escape an incoming aircraft, while its maximum diving depth of 180 metres (98 fathoms) was already more than the shallow waters it was supposed to operate in. While submerged, its top speed fell to 12 and a half knots on average (23 km/h), surfaced 9 knots of 17 km/h so it really was a pure “submarine”. Half-submerged using the snorkel, as the diesel had less capacity, speed was down to ten and a half knots or 19 km/h. Probably 4-5 knots using the creeping motor. These figures were however less impressive than or the Type XXI (17/15 kts).

However it was no all rosy. Indeed the diving time while underway was 14 seconds with a small turning circle, 150 meters regardless of the speed and estimated up to 280 meters depending on the weather. Above-water stability coef. was 0.193 meters and underwater stability 0.329 meters. Trim was however quite sensitive underwater, so much so they had the tendency to break surface after a torpedo was released, revealing its presence. On September 11, 1944, U 2324 during a troubleshooting exercise rammed a sandy seabed at 106 meters.

The diving cells in the lower “8” loop had no flood flaps and were wet by inflitrations in rough seas, so it became necessary to blow them up with compressed air from time to time, constantly checking trim as well. The low reserve displacement was just 10.5% so when water flooded in, they sank quite quickly. The “U Hai” (ex. U 2365) and “U Hecht” (ex. U 2367) showed how much. U 2331 sank off Hela on October 10, 1944 with the entire crew to also demonstrate this. Raised postwar and examined, it was proved to have been reversing and loose control. Massive infiltration completely flooded the cells and U 2331 los control, with only the commander and three bridge officers jumping out of the conning tower and saved.

Also while underwater, the small pressure hull compared to the number of sailors was an issue. The air content was around 130 m³ and with a crew of 14, the CO2 in breathing went to 1.5% after 4.5 hours. Thus, the Type XXIIII carried 400 containers of quicklime for the air purification system to scrap CO2 content and limit it to 1.5% after 5 hours, usable over 83 days. There were also 200 liters of oxygen in bottles at 150 atm, good enough if the boat was trapped at the bottom over 70 hours of three days, still for a crew of 14. It was used when oxygen content fell below 17.5%.

Armament

Due to limited space aboard, the forward bow section being very short had only two torpedo tubes with the torpedoes pre-loaded at port before depoarting. No space for spares. Unlile previous U-Boats which had built-in wells to crane down torpedoes and lead them to the torpedo room, in thzat case the reloading necessitated to ballast the submarine down at the stern, lifting the bow clear of the water while a barge with a simple A frame jack could approach and load the torpedoes directly into the tubes. This operation needed some time and exposition, which given the allied air superiority in 1944, was not easy to obtain. But it required little to no installations, and could be perform anywhere, preferrably at night.

Due to limited space aboard, the forward bow section being very short had only two torpedo tubes with the torpedoes pre-loaded at port before depoarting. No space for spares. Unlile previous U-Boats which had built-in wells to crane down torpedoes and lead them to the torpedo room, in thzat case the reloading necessitated to ballast the submarine down at the stern, lifting the bow clear of the water while a barge with a simple A frame jack could approach and load the torpedoes directly into the tubes. This operation needed some time and exposition, which given the allied air superiority in 1944, was not easy to obtain. But it required little to no installations, and could be perform anywhere, preferrably at night.

The torpedoes were of the G7e type, TIII, but other models were tested.

The standard torpedo provided to the Type XXIII was the heavy electric torpedo T IIIa FAT 2.

Improvements of the G7e(TII) the III was Introduced in 1942, a vast improvement as its former faulty exploder was replaced by a new design, it had now a range of 7,500 m (8,200 yd) up to 56 km/h (30 kn). Unlike previous models, the TIII was used for day-attacks, with a good proximity feature, so to exploded under the keel of a targeted ship, breaking its back with a single torpedo. For the XXIII and its only two torpedoes, this was the perfect match. The TIII by the time was upgraded to the steering FaT (Flächenabsuchender Torpedo) pattern running systems for convoy attacks. The Type XXIII probably also tested, but not adopoted the LuT (Lagenunabhängiger Torpedo) G7e TIII. The

Other models were tested. Designed and tested as Gothenhafen station (later captured by the Soviets), the T4/5 entered service in 1943 and Weighted at least 3,080 lbs. (1,937 kg), the T10 being 3,571 lbs. (1,620 kg) for 23 ft. 7 in. (7.186 m) in overall lenght. They carried a 440 lbs. (200 kg) warhead filled with Hexanite at 5,470 yards (5,000 m) and 30 knots on T-10 and 6,230 yards (5,700 m) at 24-25 knots for the T11, powered by Lead-acid batteries.

The T10 Spinne (“spider”) was modified to use wire guidance and issued in 1944 but results were not satisfactory and it was not adopted. The T11 Zaunkönig 2 which was less influenced by Foxer (towed noise maker). The earlier T5 Called the original Zaunkönig (wren) was designed to home in on cavitation noise (around 24.5 kHz, props at 10-18 knots). Combat debut was successful in September 1943. The T5b was had a range of 8,750 yards (8,000 m) at 22 knots but according to documentation, if tested also, they were not adopted in service by the Type XXIII.

Completed boats and fate

The first 49 boats (U-2321 to U-2331, and U-2334 to U-2371) were assembled at Deutsche Werft in Hamburg, but the U-2332 and U-2333 were ordered from Friedrich Krupp at Germaniawerft, Kiel. 29 more, U-2372 to U-2400 were ordered from Deutsche Werft yard at Toulon, but 9 were scrapped incomplete, the other never laid down. 60 were ordered aboard, including 30 at Genoa under German occupation, U-2401 to U-2430, 15 at Monfalcone U-2431 to U-2445 and 15 at Nikolaev and Linz (U-2446 to U-2460) all cancelled and never laid down. The next U-2461 to U-2500 were only on paper, they were never ordered.

The first 49 boats (U-2321 to U-2331, and U-2334 to U-2371) were assembled at Deutsche Werft in Hamburg, but the U-2332 and U-2333 were ordered from Friedrich Krupp at Germaniawerft, Kiel. 29 more, U-2372 to U-2400 were ordered from Deutsche Werft yard at Toulon, but 9 were scrapped incomplete, the other never laid down. 60 were ordered aboard, including 30 at Genoa under German occupation, U-2401 to U-2430, 15 at Monfalcone U-2431 to U-2445 and 15 at Nikolaev and Linz (U-2446 to U-2460) all cancelled and never laid down. The next U-2461 to U-2500 were only on paper, they were never ordered.

Later as these foreign yards were no longer available, production swapped to Germany: 100 were ordered to Deutsche Werft and 500 at Hamburg yard (U-4001 to U-4500), 120 ordered and laid down but scrapped incomplete, the remainder all cancelled. 300 were ordered at Kiel (U-4701 to U-5000), 11 (U-4701 to U-4712) built but U-4713 to U-4891 cancelled. U-4892 to U-5000 were only listed; never ordered.

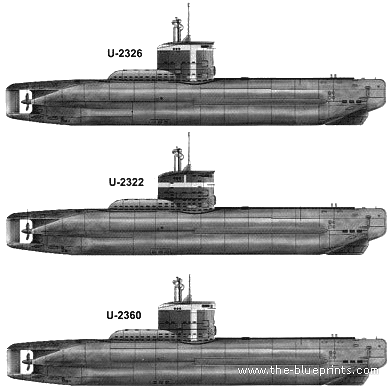

U-2321 was the first launched, at Deutsche Werft (Hamburg) on 17 April 1944. Later joined by six more completed in time for training and operational patrols around the British Isles, by early 1945. 48 more from Deutsche Werft, 14 from Germaniawerft were also completed, prepared for training, but none were truly operational. U-4712 was the last one launched on 1 March 1945 before the city was captured. U-2321, U-2322, U-2324, U-2326, U-2329 and U-2336 were all sunk on patrol while claiming four ships (7,392 gross register tons) but seven were lost in all, by air, mines, ships, or scuttling. That was needless to say, not impressive for the scale and cost of the whole program.

Seehund. This midget type carried exactly the same armament as a Type XXIII, and was far cheaper to produce. It could be also transported by rail on a single flatcar. This emergency midget built by Germaniawerft and Schichau, CRD-Monfalcone and Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz (Ulm) only measured 12 m long for 1,68 m wide and 17 tons, with an all-electric drive for 7 knots, surfaced 3 knots submerged, 500 km or 310 miles range, crew of two. 1,000 were planned, 285 completed, 138 “active”, 38 lost. Most successful attack was from IJmuiden on 31 December 1944. 142 sorties made until April 1945 and from 93,000 to 120,000 gross tons sunk depending on the sources. This was way more than the Type XXIII, showing that Dönitz could have swapped directly on this type in 1943 instead of the more complicated Elektoboote. Way more could be operated by the same crews. Indeed the manpower for a single Type XXIII was enough to man six of them. There were no tubes, so the acoustic torpedoes were just released and self-propelled to target.

Seehund. This midget type carried exactly the same armament as a Type XXIII, and was far cheaper to produce. It could be also transported by rail on a single flatcar. This emergency midget built by Germaniawerft and Schichau, CRD-Monfalcone and Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz (Ulm) only measured 12 m long for 1,68 m wide and 17 tons, with an all-electric drive for 7 knots, surfaced 3 knots submerged, 500 km or 310 miles range, crew of two. 1,000 were planned, 285 completed, 138 “active”, 38 lost. Most successful attack was from IJmuiden on 31 December 1944. 142 sorties made until April 1945 and from 93,000 to 120,000 gross tons sunk depending on the sources. This was way more than the Type XXIII, showing that Dönitz could have swapped directly on this type in 1943 instead of the more complicated Elektoboote. Way more could be operated by the same crews. Indeed the manpower for a single Type XXIII was enough to man six of them. There were no tubes, so the acoustic torpedoes were just released and self-propelled to target.

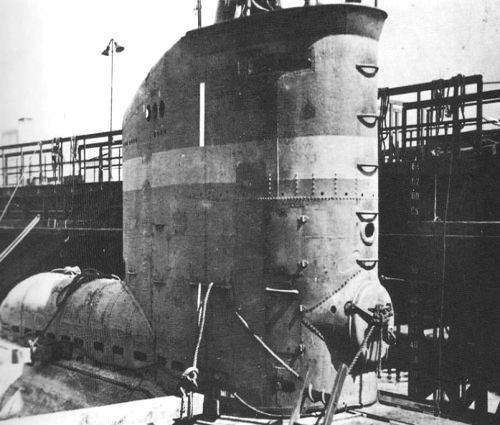

Captured Type XXIII by a Polish escort in 1945

Author’s illustration

⚙ Type XXIII specifications |

|

| Displacement | 234t/258t surfaced/submerged |

| Dimensions | 34.68 x 3.02 x 3.66m (113 ft 9+1⁄2 in x 9 ft 11 in x 12 ft) |

| Propulsion | MWM RS134S 6-cyl. diesel 621 shp, AEG GU4463-8 EM 572 shp, BBC CCR188 ECM 35 shp |

| Speed | 9.7 kn (18.0 km/h) surfaced, 12.5 kn (23 km/h) submerged |

| Range | 2,600 nmi (4,800 km)/8 kn surfaced, 194 nmi (359 km)/4 kn submerged |

| Armament | 2 bow torpedo tubes, no reloads G7e T5b |

| Max depth | 180 m+ (590 ft) |

| Crew | 14–18 |

Operational History

Due to very few being ready for combat, this section will concentrate only on those in actual war patrols. Apart the seven lost in action, by May 1945, thirty-one Type XXIII which had no crews or were in training, were scuttled. 20 however were surrendered to the Allies. Later they were sunk in Operation Deadlight, a British mass scuttling. Some ended as war prizes and were studied such as U-2326 (British N35), and U-2353 (N31) and then the Soviet submarine M-51 (Potsdam Agreement, another supposed refloated 1948), while U-4706 was attibuted to Norway and was renamed “Knerter”.

U 2322 was the first submarine of the XXIII series prepared for combat by July 1944 in Kiel, inspected by the commander-in-chief, Grand Admiral Doenitz. By October 1944, the crews of the submarines U 2322 and U 2324 were the first to successfully complete training. The training of the crew of U 2321 was delayed due to the their submarine still testing. U 2323 hit and mine and sank on July 29, 1944. On December 20, 1944, U 2324 was ready for service at Deutsche Werft, fitted with her snorkel and torpedoes. She was sent to Kiel to test the snorkel and torpedo tubes and by early January 1945, at the shipyard measures were taken to make the head of the snorkel stealthier with a special coating (porous rubber) radar wave absorbent efficient on 2/3 for locators operating in the centimeter range.

Hecht, former U-2365, modernized as SS-171 (unofficial Type 200), later sunk in 1966. The experience helped designing the Type 201.

In 1956, the Bundesmarine raised U-2365 (scuttled Kattegat 1945) and U-2367 (off Schleimünde after collision). They were repaired, modernized, and recommissioned as U-Hai (Shark) and U-Hecht (Pike) S 170 and S 171 and constituted the basis for cold war designs such as the Type 201. However the first famously sank in a gale off the Dogger Bank by September 1966 a tragedy that led to considerable improvements passed onto the Type 206 submarine.

U-2321

U-2321

U-2321, operating from the Kristiansand Norwegian base, and sank the coaster Gasray on 5 April 1945 off St Abbs Head. It was nearly a month after leaving Horten Naval Base and it was her first and only victory. The 1,406 GRT steamship was unescorted. Four days later she repoted back at Kristiansand, and was still berthed when Germany surrendered on 9 May. She was interned at Loch Ryan in Scotland and her decaying hull was used for naval gunfire by 27 November 1945 with others.

U-2322

U-2322

The first Type XXIII to achieve combat success was U-2322, commanded by Oberleutnant zur See Fridtjof Heckel. She left Horten Naval Base, Norway, on 6 February 1945, for the East coast of Scotland, and waited off St Abb’s Head, to prey of lone coastal vessels, always unescorted. On 25 February off Holy Island, she spotted and torpedoed the 1,317 GRT steam merchant Egholm with a single torpedo. This was her first and only success. Her second patrol was off East Anglia in April but for naught against well protected convoys. She surrendered at Stavanger and ended in Loch Ryan for disposal and ended as target in Operation Deadlight, towed out to sea on 27 November.

U-2323

U-2323

U2323 was operational but after just eight days in service, she was lost off the German coastline under heavy Royal Air Force air-dropped mining on 26 July 1944, off Möltenort, at the entrance to Kiel. That was her maiden voyage. 2 were killed as she was surfaced, the rest escaped to shore. She was raised in early 1945, and captured while in repair in Kiel on V-Day and BU postwar. She was part of 4th U-boat Flotilla, commissioned on 26 July 1944 and served under Lt.z.S. Walter Angermann on 18 – 26 July 1944.

U-2324

U-2324

She wa spart of the 4th U-boat Flotilla after commission, from 25 July to 14 August 1944, then the 32nd U-boat Flotilla 15 August 1944 to 31 January 1945 and 11th U-boat Flotilla from 1 February to 8 May 1945 under Lt.z.S./Oblt.z.S. Hans-Heinrich Haß and Kptlt. Konstantin von Rappard. She made only two patrols from 29 January to 25 February 1945 and 2 April to 8 May 1945. She left Kiel for her first war patrol on 18 January 1945. Her second was from Stavanger. She had no kills, and ended in Loch Ryan and Operation Deadlight, sunk as target on 27 November.

U-2325

U-2325

She served with the 4th U-boat Flotilla (3–14 August 1944), 32nd (15 August 1944–31 January 1945), 11th (1 February–8 May 1945) under Oblt.z.S. Wolf-Harald Schüer and Oblt.z.S. Kurt Eckel. No patrols, she surrendered on 9 May 1945 at Kristiansand. Loch Ryan, sunk in Operation Deadligh by the British destroyer HMS Onslow and Polish destroyer ORP Błyskawica.

U-2326

U-2326

Commissioned on 10 August 1944, 4th U-boat Flotilla (10–14 August 1944), 32nd (15 August 1944-31 January 1945) and finally 11th (1 February–8 May 1945) under Oblt.z.S. Karl Jobst making two patrols on19 – 27 April 1945 and 4 – 14 May 1945; no kills, surrendered 8 May, but unusual fate: Interned in Dundee, Scotland, British N35, transferred to France in 1946 but sunk 6 December 1946, accident in Toulon (whole crew lost). Now a war grave.

U-2327

U-2327

Commissioned on 19 August 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla (19 August 1944–2 May 1945) under Oblt.z.S. Heinrich Mürl, Werner Müller, Hans-Walter Pahl, Hermann Schulz, used for training. On 2 May 1945, scuttled at Kiel (Operation Regenbogen) raised and BU postwar.

U-2328

U-2328

Commissioned on 25 August 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla (25 August 1944 – 1 April 1945), 11th (1 April – 8 May 1945) under Oblt.z.S. Hans-Ullrich Scholle, Peter Lawrence. No sortie, no victory, surrendered at Bergen, Norway, transferred to Loch Ryan 30 May 1945, selected for Operation Deadlight, sunk 27 November 1945 while in tow.

U-2329

U-2329

She was commissioned on 1 September 1944, served with the 32nd U-boat Flotilla (1 September 1944 – 14 March 1945) and 11th (15 March – 8 May 1945) all under Lt.z.S./Oblt.z.S. Heinrich Schlott. On single patrol, no kill. She surrendered at Stavanger, interned in Loch Ryan June 1945, selected for Operation Deadlight sunk by gunfire 28 November 1945 by HMS Onslow and ORP Piorun.

U-2330

U-2330

Commissioned 7 September 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla (7 September 1944 – 15 March 1945), 11th (16 March – 3 May 1945) under Oblt.z.S. Hans Beckmann, no sortie, scuttled on 3 May 1945, at Kiel (Operation Regenbogen), raised, BU postwar.

U-2331

U-2331

Commissioned 12 September 1944, was working-up in the Baltic under Oberleutnant zur See Hans-Walter Pahl and Klaus Vernier as tactical expert. On 10 October she failed to surface off the Hel Peninsula, 4 including the captain escaped, 15 including Vernier died with her. An investigation revealed the order to submerge whilst travelling in reverse caused unbalanced and to sink uncontrollably. Only men in the conning tower survived. Wreck raised and scrapped.

U-2332

U-2332

Commissioned 13 November 1944, 5th U-boat Flotilla under Oblt.z.S. Dieter Bornkessel, scuttled in Kiel 3 May 1945, Operation Regenbogen. Raised, BU postwar.

U-2333

U-2333

Commissioned 18 December 1944, 5th U-boat Flotilla from 18 December 1944 under Oblt.z.S. Heinz Baumann, scuttled 5 May 1945 in Gelting Bay (Operation Regenbogen), later raised and BU.

U-2334

U-2334

Commissioned 21 September 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 1 April 1945 then 11th until 8 May 1945 under Lt.z.S. / Oblt.z.S. Walter Angermann. Surrendered at Kristiansand, Loch Ryan, sunk at Operation Deadlight 28 November 1945.

U-2335

U-2335

Commissioned on 27 September 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 1 April 1945, then 11th until 8 May 1945 under Lt.z.S./Oblt.z.S. Karl-Dietrich Benthin, surrendered at Kristiansand, Loch Ryan, sunk at Operation Deadlight.

U-2336

U-2336

U-2336 (Kapitänleutnant Emil Klusmeier)

U-2336 sank the last Allied ships in the European war, on 7 May 1945, sending to the bottom the freighters Sneland I and Avondale Park off the Isle of May, one with a single torpedo eacn, and inside the Firth of Forth. Which was heavily patrolled. The Sneland I and the Avondale Park were hit at 23:03, an hour before the official German surrender, making the Avondale Park, the last merchant ship ever sunk by a U-boat. Kapitänleutnant Klusmeier was later accused to have ignored orders, but claimed he never received news of the ceasefire. Fortunately, sailors of both vessels could regain the shore or were rescued as the area was packed with ships and boats.

U-2337

U-2337

Commissioned 4 October 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla from 4 October 1944 to 8 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Günter Behnisch, surrendered at Kristiansand, same fate as the others above.

U-2338

U-2338

Commissioned 9 October 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 4 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Hans-Dietrich Kaiser, sunk during her only sortie on 4 May 1945, east northeast of Fredericia by British Beaufighters of 236 Squadron and 254 Squadron. 12 killed, 2 survivors. Raised in 1952, BU.

U-2339

U-2339

Commissioned 16 November 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 1 December 1944, 8th U-boat Flotilla until 15 February 1945, 4th U-boat Flotilla until 5 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Germanus Woermann. Scuttled in Gelting Bay (Operation Regenbogen).

U-2340

U-2340

Commissioned 16 October 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 30 March 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Emil Klusmeier, sunk by British bombs at Hamburg. Wreck later raised, BU.

U-2341

U-2341

Commissioned 21 October 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 5 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Hermann Böhm, surrendered at Cuxhaven, transferred to Lisahally (Northern Ireland) 21 June, sunk at Operation Deadlight, 31 December 1945 by gunfire.

U-2342

U-2342

Commissioned 1 November 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 26 December 1944 under Oblt.z.S.d.R. Berthold Schad von Mittelbiberach. U-2342 was travelling in a convoy of ten boats with supplies and personnel to Norway. North of Swinemünde, she triggered a RAF air-dropped mine and the damage made her sinking dlowly, enough for rescue vessels to to get all but seven sailors including captain von Mittelbiberach. The wreck was blew up in 1954 to clear the seaway.

U-2343

U-2343

Commissioned 6 November 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 15 February 1945, 4th until 5 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Harald Fuhlendorf and Kptlt. Hans-Ludwig Gaude, scuttled in Gelting Bay, Operation Regenbogen, later raised, BU.

U-2344

U-2344

Commissioned 10 November 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 18 February 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Hermann Ellerlage, during her first and only patrol she was lost on 18 February 1945 after a collision with sister ships U-2336. 11 of the 14 died. Wreck raised 1956, BU at Rostock 1958.

U-2345

U-2345

Commissioned 15 November 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 8 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Karl Steffen. Surrendered at Stavanger, Loch Ryan, Operation Deadlight, sunk 27 November 1945.

U-2346

U-2346

Commissioned 20 November 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 15 February 1945, 4th until 5 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Hermann von der Höh, scuttled in Gelting Bay.

U-2347

U-2347

Commissioned 2 December 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 15 Februar, 4th until 5 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Willibald Ulbing, scuttled in Gelting Bay.

U-2348

U-2348

Commissioned 4 December 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 15 February 1945, 4th until 8 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Georg Goschzik, surrendered at Stavanger, Loch Ryan, survived Operation Deadlight, towed back, BU in Belfast April 1949.

U-2349

U-2349

Commissioned on 11 December 1944, 32nd U-boat Flotilla until 15 February, 4th until 5 May 1945 under Oblt.z.S. Hans-Georg Müller, scuttled in Gelting Bay.

From U-2350 to U-2360, fates and assignations are about the same (32nd and 4th flotillas). None made any sortie nor kill. They ended either scuttled at Gelting Bay or surrendered in Norway, or Flensburg, many being sunk during the “turkey shoot” of Operation Deadlight, mosttly perform to study the resistance of submarines to gunfire. U-2352 was scuttled in the Hørup Hav, southeast of Sønderborg. U-2353 was later transferred to Loch Ryan but allocated to the Soviet Union, sent in Libau, as the former British N31, passed onto the Baltic fleet on 13 February 1946 as M-51 by 9 June 1949, tested, reserve fleet on 22 December 1950 as training hulk, stricken 17 March 1952, BU 1963. U-2355 was scuttled northwest of Laboe, U-2356 surrendered at Cuxhaven, but on 2 May 1945, U-2359 (Oblt.z.S. Gustav Bischof) was sunk while in transit to the Kattegat by Mosquitos of British 143 Squadron, 235 Squadron, 248 Squadron, Canadian 404 Squadron, and Norwegian 333 Squadron using rockets, one of the few occurences of such “kills”. She sunk with all hands.

Next for U-2361 to U-2371 (2370 never operational), and U-4701 to U-4712: U-2365 was scuttled northwest of Anholt in the Kattegat, later she was raised and repaired and became Hai (S 170) and U-2237 became Hecht. But sunk near Schleimünde after a collision with another unidentified U-boat. U-2371 was scuttled at Hamburg. The others just had the same fate as above, most having barely the time working out or training before surrendering or being scuttled.

Foreign Users

French Marine Nationale: In addition to the Type XXI boat U 2518, the French Navy also took over a Type XXIII boat, U 2326, acquired from Great Britain in February 1946. After overhaul at Cherbourg by April 1946 and Lorient, she was moved to Toulon but lost off the coast on December 5, 1946 due to a diving accident, without survivors.

Royal Navy: Some of the Type XXIII submarines delivered to Great Britain after the end of the war were not destroyed in Operation Deadlight, but were selected by the Royal Navy for testing purposes. After a short time, these boats were given to allied navies or scrapped.

Soviet Navy: Due to the flight of the German submarines to the west, the advance of the Western Allies and finally the manner in which the occupation zones were divided, the Type XXIII submarines and their production facilities were beyond the reach of the Red Army. Consequently, the Soviet Union could only acquire a Type XXIII submarine by demanding a share in the British spoils of war. The Royal Navy eventually handed over N 31 (formerly U 2353) to the Soviet Navy. N 31 moved to Libau on November 23, 1945 under the Soviet flag. The British name was retained, but was written in Cyrillic as н 31. With the scrapping of the boat in 1963, the last Type XXIII unit ceased to exist outside of Germany.

Norwegian Navy: The U 4706, which was unroadworthy in Kristiansand at the end of the war, was first handed over to British spoils of war in May 1945 and finally to the Norwegian Navy in October 1948, which already had three German Type VII C captured submarines. At this point, U 4706 was the last intact Type XXIII submarine built at the Germania shipyard in Kiel. Due to a fire, the planned commissioning of U 4706 as KNM Knerten did not take place. Instead, the Hulk was first handed over to Kongelig Norsk Seilforening (KNS) on April 14, 1950 and finally scrapped in 1954. This means that U 4701 was scrapped just a few years too early to be considered for repair and commissioning in the Federal Navy through a buyback.

Volksmarine (East German Navy): In the GDR in the 1950s, the nava staff also consider the re-establishment of a submarine force but events of June 17, 1953 brutally changed minds and former submariners at Sassnitz were assigned to other units. The raising of U 2344 which sank off Heiligendamm in a collision with U 2336 on February 18, 1945 was done by June 1956 and she was placed in a floating dock at the Neptun shipyard in Rostock, duly examined. No repairs or recommissioning took place. At some point she was tp be used as underwater target ship for the Volksmarine’s sub-hunters, but instead she was scrapped in Rostock in 1958.

Read More/Src

Books

Busch, Rainer; Röll, Hans-Joachim (1999). German U-boat commanders of World War II. Greenhill Books NIP

Busch, Rainer; Röll, Hans-Joachim (1999). Deutsche U-Boot-Verluste von September 1939 bis Mai 1945. Vol. IV. Hamburg, Berlin

Gröner, Erich; Jung, Dieter; Maass, Martin (1991). U-boats and Mine Warfare Vessels. German Warships 1815–1945. Vol. 2. Conway Maritime Press.

Sharpe, Peter (1998). U-Boat Fact File. Great Britain: Midland Publishing.

Links

Wolf pack : the story of the U-boat in World War II by Williamson, Gordon, 1951-;

Helgason, Guðmundur. German Type XXIII, U-boats of WWII – uboat.net.

en.wikipedia.org Type XXIII submarine

on wehrmacht-history.com

military.wikireading.ru one of the best sources, with plans

navweaps.com/ german torpedoes

Videos

Model Kits

https://reviews.ipmsusa.org/review/german-u-xxiii-coastal-submarine

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Russkiy Flot

Russkiy Flot French Naval Aviation

French Naval Aviation Russian Naval Aviation

Russian Naval Aviation Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN IDF Navy

IDF Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

RN

RN

Marine Nationale

Marine Nationale

Soviet Navy

Soviet Navy

dbodesign

dbodesign